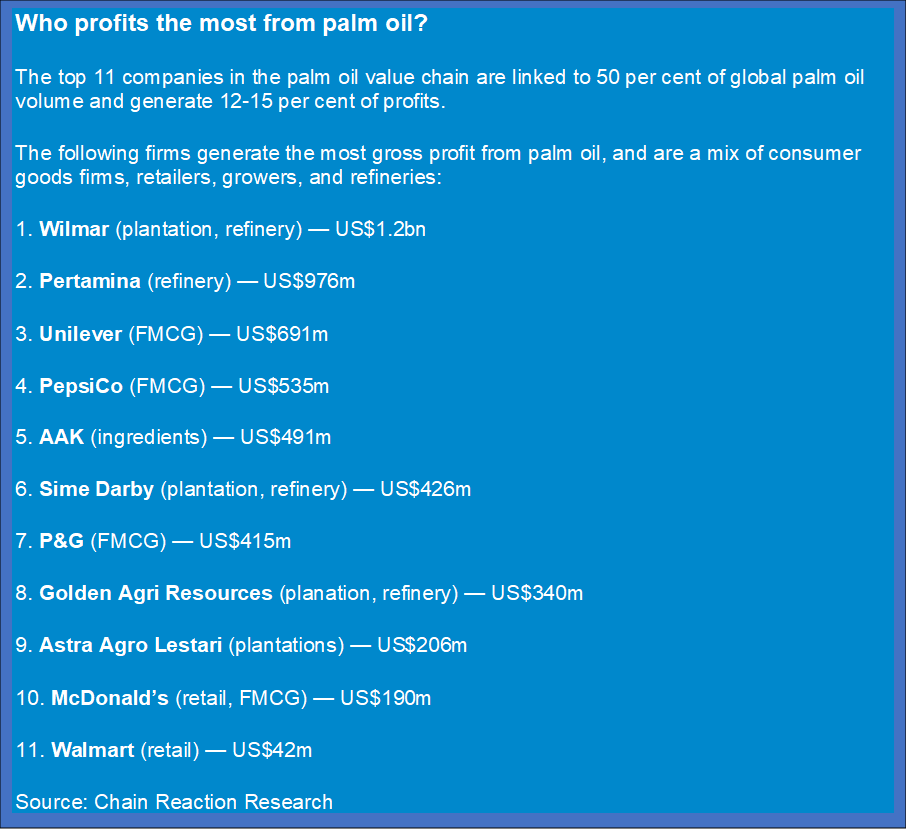

If the likes of Unilever, Procter & Gamble and PepsiCo charged slightly more for their products or dipped into the huge profits they make from palm oil to support smallholder farmers, the sector could almost eliminate deforestation, a new report finds.

The public debate on palm oil has often centred on large corporate entities driving the industry, ignoring the fact that smallholders play a critical role in the sector. Image: Shutterstock, By Robin Hicks, June 15, 2021

The seemingly impossible task of decoupling deforestation from the palm oil industry could be achieved by raising the price of palm-based consumer goods by just 1.8 per cent, a new report from risk analysis firm Chain Reaction Research (CRR) suggests.

The additional revenue consumer goods firms make from the sale of products such as instant noodles, lipstick, ice cream and shampoo could go into helping growers implement zero-deforestation commitments with better monitoring and verification, and provide support for smallholder farmers to grow palm oil without encroaching on forests.

Three palm oil firms were responsible for a quarter of deforestation in Indonesia, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea in 2020

Some consumer good companies with higher profit margins, such as Procter & Gamble, could raise the price of products by 0.15 per cent to cut forest loss out of their palm oil value chain, while cooking oil brands with smaller margins would have to raise their prices by more, the study published on Tuesday finds.

Alternatively, the downstream consumer goods companies, could dip into the vast profits they generate from palm oil to tackle deforestation in grower countries such as Indonesia or Malaysia.

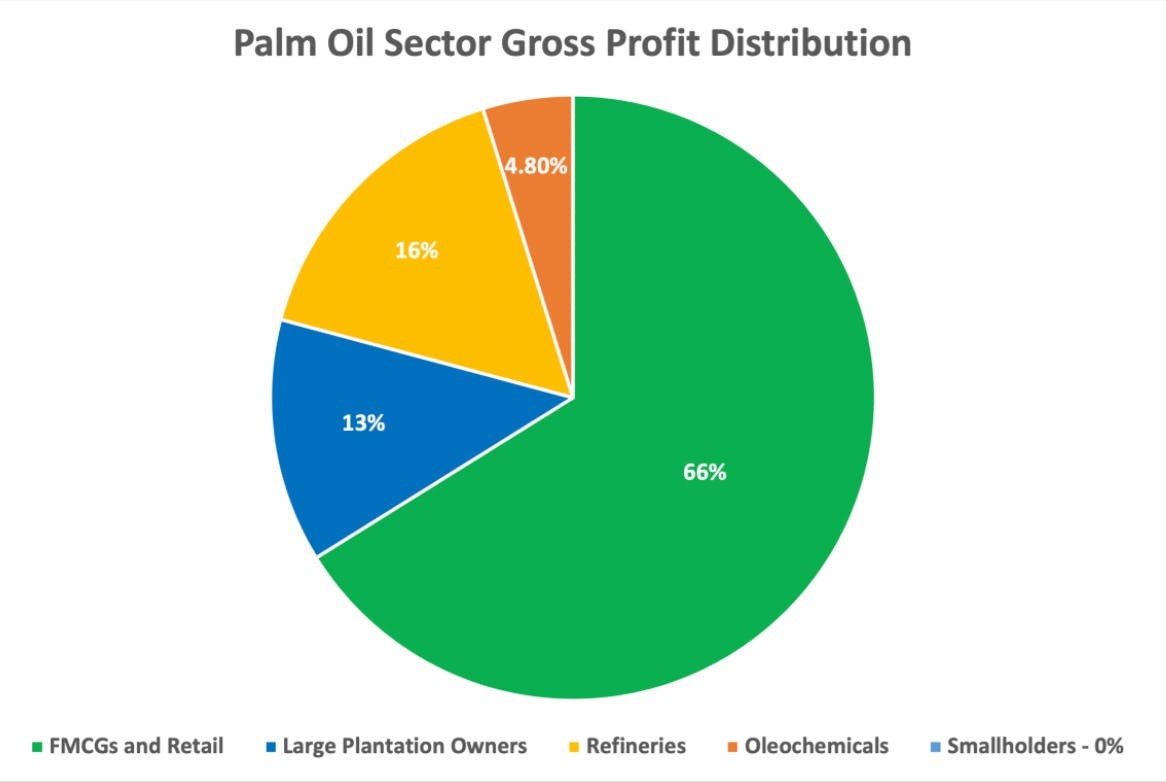

CRR’s report finds that the consumer goods firms, that sell palm oil-based products, and retailers, claim two-thirds of the profits, some US$20 billion, from the palm oil value chain. Large plantation owners, refineries and oleochemicals firms claim smaller portions of the profits, while smallholders claim none of the profits (see chart).

Smallholders, which generate six per cent of the palm oil market’s value, or US$17 billion, tend to be poorly resourced and unproductive, generating around half of the yield of large-scale commercial farms. They are also the main drivers of rainforest loss in Indonesia, the world’s largest palm oil producer market, according to satellite analysis by Starling, a monitoring tool.

Smallholders earn an average of US$7,540 a year, and lack access to the finance needed to support sustainable cultivation methods. If consumer goods brands and retailers invested more in the smallholders that supply them, with cash-flow support for sustainable production for instance, deforestation could be all but eliminated from the palm oil value chain, the report finds.

Many smallholders will need to replace ageing trees in the coming years, and need financial support while new trees reach maturity. Planting costs and loss of cash flow will cost US$1.1 billion per year for the next 25 years, according to CRR data.

Implementing effective zero-deforestation pledges will cost more. CRR estimates that industry-best monitoring and verification methods to deliver deforestation-free palm oil will cost US$65 per tonne, or US$4.9 billion.

In total, removing deforestation from the palm oil value chain will cost US$6 billion a year.

Slow-moving consumer goods firms?

Downstream companies currently invest relatively little in weeding out deforestation from their supply chains, despite high-profile sustainability commitments, CRR’s research finds.

According to a 2020 study, 88 per cent of the top 25 consumer goods firms are lagging in the execution of no-deforestation pledges, and spending on programmes to combat deforestation is low. Industry-best efforts to eliminate forest loss would cost about 0.1 per cent of palm oil-related product revenues, according to CRR.

The Consumer Goods Forum, a collective of consumers goods firms worth US$4.2 trillion in sales, pledged in 2010 to be deforestation-free by 2020. Having missed that target, some set new ones.

Consumer goods company Unilever now promises to be deforestation-free by 2023, and has invested in supporting smallholders. Mars, a confectionery company, claimed to be deforestation-free last year by cutting ties with hundreds of smaller suppliers that didn’t meet its sustainability standards.

Meanwhile, the likes of Unilever, Nestlé, Mars, PepsiCo, Mondelêz, and Kellogg’s continue to suffer brand damage from forest destruction revelations in palm oil producing countries. In 2019, suppliers to these companies were found to be linked to illegal forest clearing in Indonesia’s Leuser ecosystem, one of Southeast Asia’s most ecologically important rainforests.

“The global brand FMCGs [fast-moving consumer goods] should feel most responsible [for deforestation],” said Gerard Rijk, an analyst for Profundo, and lead author of the study. “They have the largest market capitalisation, and their brands have the most to lose in reputational value, so there should be an incentive [to invest more in efforts to end deforestation].”

“These companies are earning 66 per cent of profits in the palm oil supply chain, and so they could really contribute to a solution instead of telling the world that it is too expensive to check, to support or to segregate [deforestation-free palm oil],” said Rijk. The former head of sustainability for the largest grower of certified sustainable palm oil, Sime Darby, has complained that palm oil buyers are unwilling to pay a premium for sustainable palm.

Aida Greenbury, senior sustainability advisor at the Indonesian Palm Oil Smallholder Union (SPKS), said that consumer goods firms have profited from palm oil at the expense of forest landscapes and local communities for generations, and the damage being done must be paid for.

She called on consumer goods firm to introduce better traceability systems to track the palm oil they use back to the smallfarmers who grow it, to incentivise sustainable production, and allocate at least 2 per cent of their profits to address their deforestation footprints, including forest conservation schemes that benefit smallholders and local communities.

English

English Indonesia

Indonesia